When you look to expand your home network, especially for wired clients, you will likely need a couple of network switches. This post explains them in simple terms and helps you get started with one.

Before continuing, it’s a good idea to understand what a router is, though you’ll get a quick refresh below.

Dong’s note: I first published this piece on May 2, 2025, and last updated it with the latest information on December 4, 2025.

Network switches: The straightforward way to expand a wired network

To have a local network, you first need a router with a wide-area network (WAN) port to connect to the Internet and several local-area network (LAN) ports to host wired clients, such as a desktop computer, a game console, or, well, a network switch.

So, a network switch is first and foremost a wired device itself. However, it’s a special one because its primary job is to add more LAN ports to the router, allowing the system to host more wired devices.

“Primary” because a switch can do more than that, but in all cases, the extra network ports are the primary purpose of a switch.

Note: Many home routers also include a built-in Wi-Fi access point, but this post focuses solely on wired networking, where we use network cables to connect devices.

The uplink port

You connect one of the switch’s ports to an existing router (or switch) via a network cable, and that particular port will serve as the uplink. Now the rest operate like the router’s LAN ports. The same idea applies when you cascade (daisy-chain) multiple switches: each switch will have one uplink port.

Some switches have a dedicated uplink port, while in others, whichever port is connected to the existing router automatically serves as the uplink port. On this port front, it’s important to note:

- Generally, only one port can be used as the uplink. If you use two or more ports for that role, you might encounter unexpected issues, and at best, only one is being used. Note: In a link aggregation (LAG) setup, multiple ports can be combined into a single link. Some switches support LAG for the uplink.

- A switch can be used to extend one existing network. Using a single switch to extend two separate networks by connecting two of its ports to two routers will cause all sorts of issues, in addition to violating #1 above.

- Other than the uplink port, the rest of a switch’s ports are for separate wired devices (including other switches). It’s important to avoid using both ends of a single network cable to connect to two ports on the same switch—in this case, the system may overload and crash.

Network switches come in all different sizes, from just a few to 48 ports or even more, and, as mentioned, you can daisy-chain switches to have even more ports. The port grade determines a switch’s performance. Nowadays, Gigabit switches are the minimum (and very affordable), with Multi-Gig switches being the standard.

After that, different types of switches can do more than just add more ports. But before we continue, let’s address an old elephant in the room: the network hub.

Network switch vs. network hub

Both a network switch and a network hub can add more ports to an existing router. The main difference between them is that all ports of a hub share the same bandwidth, whereas in a switch, each port has its own bandwidth.

In a way (not entirely accurate), you can think of a network hub as a “splitter” that simply splits a single connection (to the router) into multiple ones. More technically correct: a hub copies packets from all ports to all other ports, whereas a switch copies packets between pairs of ports. The result? The more devices connected to a hub, the slower they all become, unlike a switch.

The good news is that you probably won’t need to worry if you get a network hub by mistake, as this type of device has long become obsolete.

Network switches: It’s about uncompromising local bandwidth

As mentioned, a switch also splits a connection (to the router) into multiple ones. In this case, the uplink connection—the one that connects the switch to the router— decides the uplink bandwidth for all devices connected to the switch’s other ports.

Specifically, suppose a switch’s uplink is a Gigabit connection, and you have five Gigabit wired devices connected to its LAN ports. In that case, these five devices will share this 1000Mbps uplink bandwidth when connecting to the Internet or communicating with any local network device that’s not connected to the same switch. Simple math is that each will get 200Mbps at most when all five are active at the same time.

For this reason, many switches use a faster-grade port for the uplink. For example, a Gigabit switch might have a 2.5Gbps or faster uplink port. A 2.5Gbps switch might have a 5Gbps or 10Gbps uplink port. Most consumer-grade 10Gbps switches use a 10Gbps uplink port, though enterprise-class switches may use a faster-than-10Gbps port, such as an SFP28, which supports 25Gbps.

Not sure of the difference between a typical (RJ45) network port and an SFP? The cabinet below includes a crash course.

RJ45 (BASE-T) vs. SFP

BASE-T (or BaseT) is the standard port type for data communication and refers to the 8-position 8-contact (8P8C) wiring method used inside a network cable and in its connectors at both ends.

This type is known by the misnomer “Registered Jack 45” or RJ45, which is more commonly used.

On the other hand, the SFP, nowadays with its popular SFP+ (plus) rendition, is used for telecommunication and data communication, primarily in enterprise applications. SFP stands for Small Form Factor Pluggable and is the technical name for what is often referred to as Fiber Channel or Fiber.

For data communication, an SFP+ port supports 1Gbps or 10 Gbps. The older version, SFP, supports only 1Gbps, though it uses the same port type as SFP+. This type of port standard and wiring is strict in configuration and physical attachment, offering better reliability and performance.

SFPs can also be more flexible in speed grades and can offer faster-than-10Gbps bandwidth, such as SFP28, which has a 25Gbps ceiling.

While physically different, BASE-T and SFP/+ are parts of the Ethernet family, sharing the same networking principles and Ethernet naming convention—Gigabit Ethernet (1Gbps), Multi-Gig Ethernet (2.5GBASE-T, 5GBASE-T), or 10 Gigabit Ethernet (a.k.a 10GE, 10GbE, or 10 GigE).

Generally, you can get an adapter, called a “transceiver”, to connect a BASE-T device to an SFP or SFP+ port. In this case, keep in mind that a particular adapter might only work (well) with the SFP/+ port of certain hardware vendors.

The BASE-T wiring is more popular thanks to its simple design and speed support flexibility. Some routers and switches have an RJ45/SFP+ combo, which includes two physical ports of each type, but you can use one at a time.

However, within the switch itself, connected devices can communicate without using uplink bandwidth. Specifically, the five devices connected to the switch mentioned above can all communicate with one another at full gigabit (1000Mbps).

Similarly, if you have a 2.5Gbps switch connected to a Gigabit router, the uplink is limited to 1Gbps. However, 2.5Gbps-capable devices connected to the switch can talk to one another at 2.5Gbps—they don’t engage the uplink bandwidth to the router.

That’s the beauty of a switch in terms of general bandwidth, and there’s more a switch can do.

Types and features of network switches

Besides the number of ports and port grade, you’ll notice a few additional features in network switches, such as “managed,” “unmanaged,” and ” Power over Ethernet (PoE)”. In fact, you’ll generally see all that in the model names. For example, the Zyxel XS1930-12HP is a 12-Port Multi-Gig PoE Managed switch.

Let’s find out what these mean.

What is a unmanaged network switch?

An unmanaged switch adds more ports to an existing network, and that’s it. Plug it in, and you’re good to go. All of its ports work equally. It’s a plug-and-play device that adds more ports to an existing router.

This type of switch is a perfect fit in a home or an office. All you have to do is plug its uplink port to the router, turn it on, and you’re good to go. Unmanaged switches are generally also much more affordable than managed switches.

What is a managed network switch?

A managed switch comes with additional networking features, such as QoS, content filtering, virtual network (VLAN), and more. But the gist of it is that you can program the switch’s ports to do different things.

The more the switch can do, the more expensive it becomes, reaching tens of thousands (even hundreds of thousands) of dollars. And you will need to configure these features manually.

For this reason, only big businesses generally need this type of switch. In a typical network, the router is the managed switch. (A home router is essentially a combo box of a managed switch plus the routing function, though it’s about the layers as mentioned below.)

Using a managed switch for your home might cause unexpected issues if you don’t know what you’re doing. That is especially true when you stack multiple switches on top of one another.

However, by default, most consumer-friendly managed switches operate in unmanaged mode or can be configured to act as unmanaged switches.

That’s because switches, unmanaged or not, differ by the number of “layers” they support.

Unmanaged network switches vs. managed network switches: It’s in the networking layers

Depending on who you ask, networking is organized in either seven or four layers. For the sake of simplicity, let’s go with the latter, and in either case, we only need to care about the first three.

The first layer, or layer 1, has two levels: Physical and Data Link:

- Physical level: The bare minimum required for devices to be connected. In other words, at this level, a network switch works like a splitter—it’s the network hub as mentioned above.

- Data Link level: That’s when a switch functions as an unmanaged switch that can handle packets, frames, and a few other things.

Layer 2 is the level at which a switch becomes a managed switch. It’s when the hardware has more features, including VPN, QoS, packet inspection, and more. At layer 2, a switch begins to perform some Firewall functions.

Layer 3 is called the Transport layer, and is when a managed switch has enough capacity to function as a router. In other words, all routers are technically layer-3 switches with various configurations and specs.

A router is, in fact, an advanced switch, with the uplink port serving as the WAN port that connects to the Internet. After that, its LAN ports function the same way as in any standard switch. Since most routers have only a limited number of built-in LAN ports, we need to use a switch for additional wired connections within the local network.

After that, Layer 4 adds more application support and is generally no longer applicable to any home-grade or even SMB applications. This layer also includes more advanced firewall functions.

That said, when it comes to picking a managed switch, the question is always Layer 2 vs. Layer 3, and the answer is you only need the latter if you don’t already have a router.

Layers are irrelevant when you’re looking for an unmanaged switch. The majority of managed switches you’ll find are layer-2.

The more layers a switch supports, the more expensive it is. A switch that supports more layers can always be programmed to work as if it supported fewer layers. The other way around is not possible.

Among those network layers, there’s another device: the firewall, which itself is a switch. Below is the recap of these types of special switches.

Network switch vs. firewall vs. router

These devices are all “switches” and differ by the networking layers they support.

A switch always has multiple network ports, one of which is the uplink port for an incoming network connection, shared among the rest of the switch’s ports. A switch is a physical device that connects different network layers.

A firewall is a managed switch that can inspect data packets and regulate network traffic, such as blocking, filtering, or restricting it. The firewall function starts at the networking layer 2 and extends to the higher layers, depending on its level of sophistication. Nowadays, most firewalls can also serve as routers.

A router is a managed switch whose main job is to provide and guide (or “route”) the network traffic. A router’s uplink is the WAN port that connects to the Internet. The routing function starts with the network layer 3. Nowadays, all modern routers have built-in firewalls, and an advanced router generally includes a top-tier firewall.

PoE switch

Unlike the “layers” mentioned above, PoE is available in both managed and unmanaged switches.

Short for Power-over-Ethernet, PoE is a feature where a switch’s port can power a PoE device via the same network cable. Specifically, the network cable that connects the device to the switch also delivers juice to power that device, saving users from having a separate power adapter (or a power outlet at the location of the device).

PoE has different standards in max power output per port, including PoE (15.4W), PoE+ (30W), PoE++ (60W), and PoE+++ (100W).

How to manage a switch

If you get an unmanaged switch, there’s, well, no need to manage it. Just plug its uplink port into the router (or an existing switch), and it’s ready to work.

As mentioned, most unmanaged switches have no dedicated uplink port. Whichever port you use to connect them to the existing network becomes the uplink port. Still, the rule is that, when applicable, use the port with the fastest connection grade as the uplink.

On the other hand, most managed switches have a dedicated (faster) uplink port. After that, there are a couple of scenarios:

- When a managed switch works in unmanaged mode, you can treat it as such, and there’s no need to manage it.

- If you want to take advantage of the switch features or manage its ports:

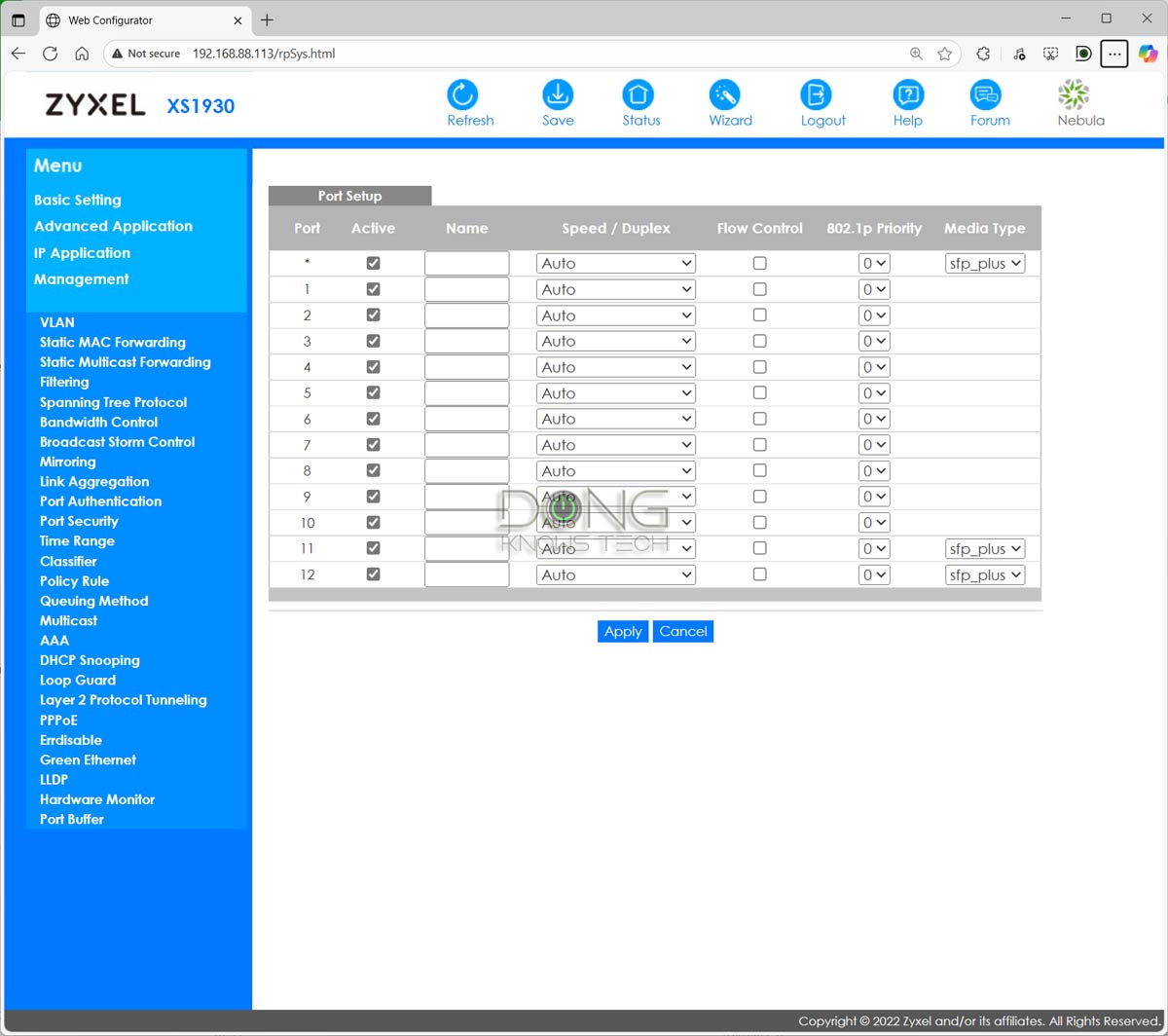

- Managed switches often come with a web user interface accessible via their IP address, which is given out by the network’s router. You need to find out this IP address first before you can access the interface.

- Some switches have a mobile app for management. In this case, run the app and follow the onscreen instructions.

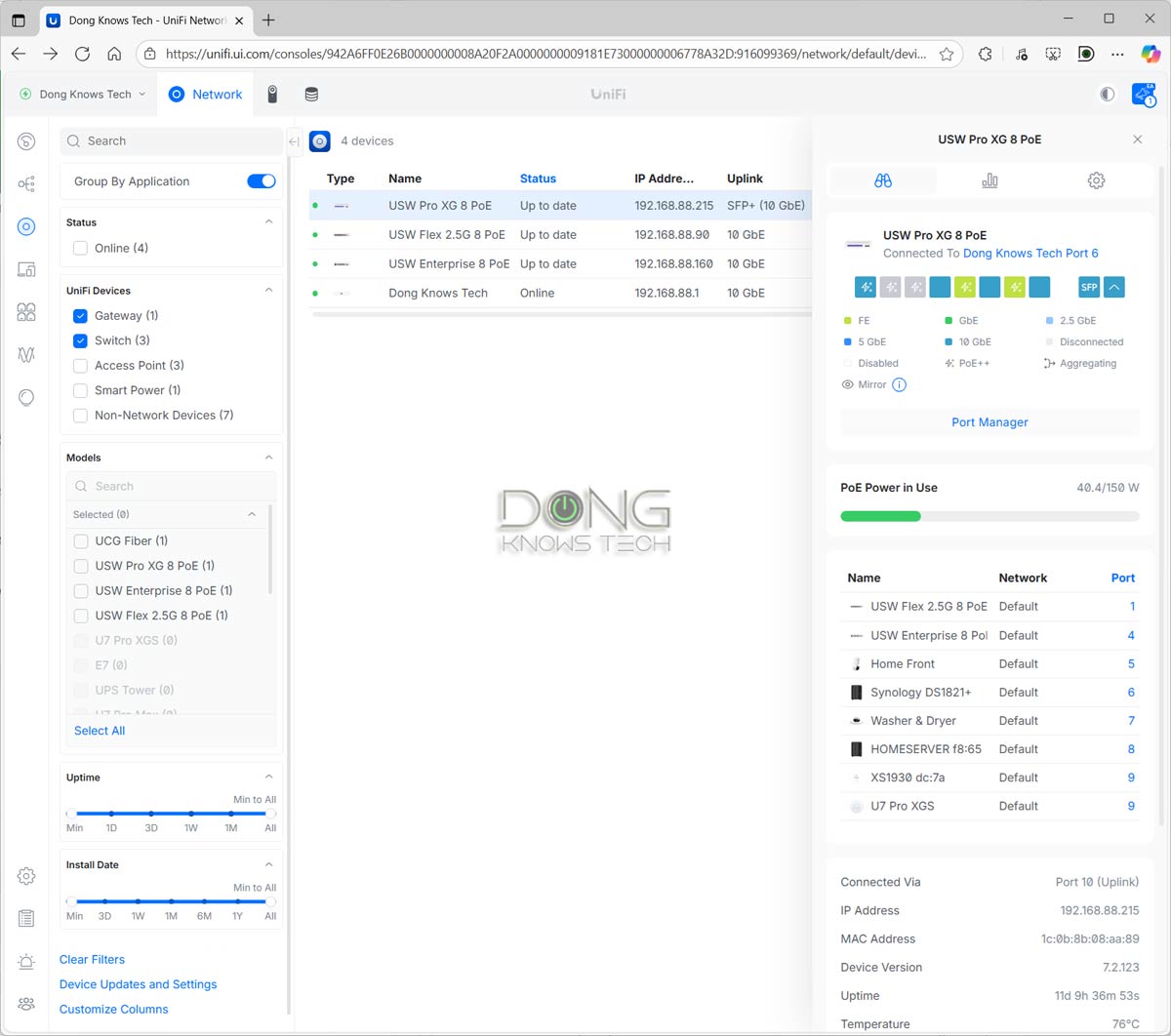

- Other switches belong to an ecosystem, such as those of Ubiquiti’s UniFi or TP-Link’s Omada. In this case, you can manage it via the system’s central location, namely the console, controller, or a special router.

That said, other than unmanaged switches, which are common, using a managed switch is always a case-by-case decision, depending on the existing network or hardware vendor.

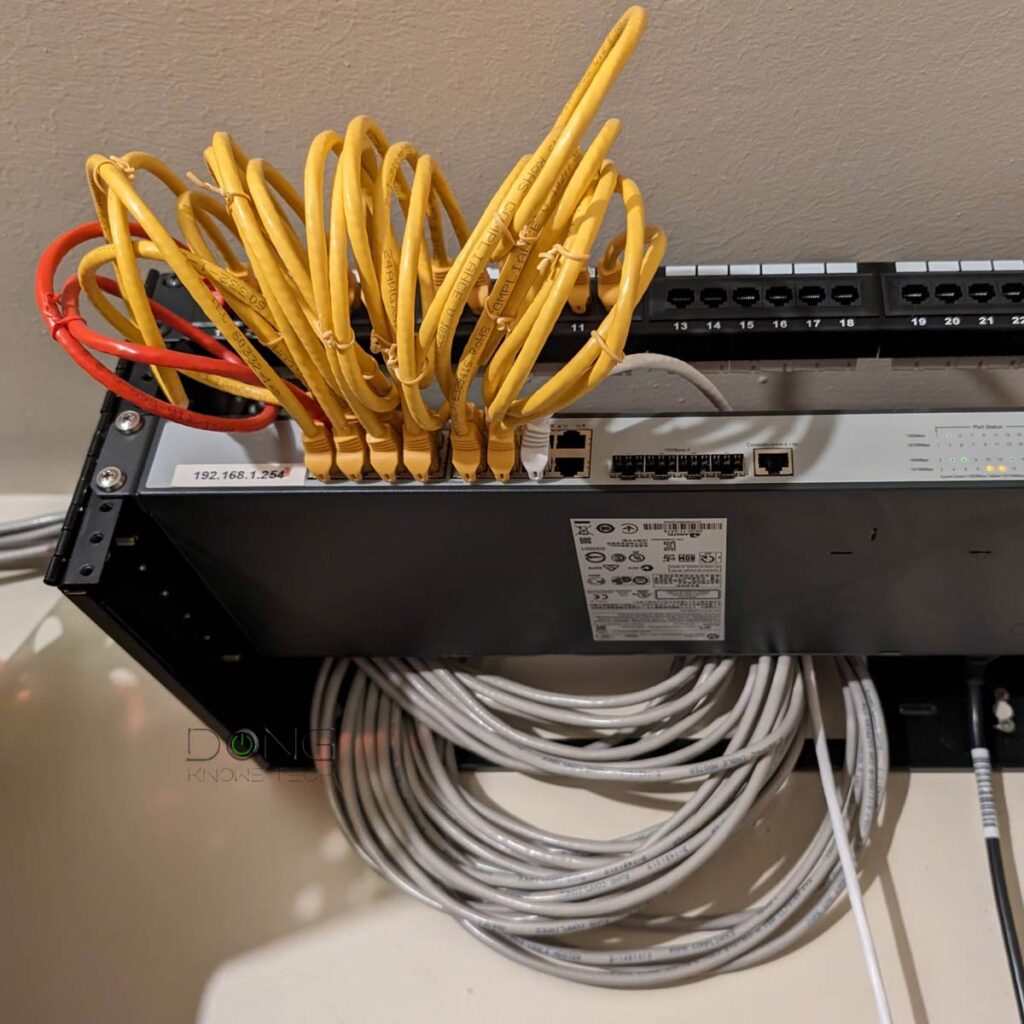

Right: The standalone web user interface of a Zyxel XS1930-12HP managed switch.

The takeaway

Switches are an easy way to expand your wired network. Along the way, some of them can add features, such as PoE support, which is excellent for IP cameras, Wi-Fi access points, and IP phones.

In any case, this is wired networking we’re talking about. So, get your home wired first! After that, check out this quick buying guide, and below is the list of the current best five switches you can safely bring home today.

Top 5 best Multi-Gig network switches

|  |  |  |  | |

| Name | Ubiquiti Switch Pro XG 8 PoE’s Rating | Zyxel XGS1250-12’s Rating | Ubiquiti UDB Switch’s Rating | Zyxel XS1930-12HP’s Rating | TRENDnet TEG-S750’s Rating |

| Price | – | – | – | – | – |

| Rating | |||||

| Description | |||||

| Statistics | |||||

| Buy this product |

I am new to your site, for now mostly reading up on Asus wifi equipment. But after reading a couple of articles I noticed how you seem to answer all (??) questions in the comments. Wow… much respect for that!

👍

Welcome to the nonsense-free zone, MKL! 🙂

Great article, as always!

One thing you might want to include is IGMP Snooping.

I bought a TP-Link LS1008G switch that caused issues with IPTV. After some research, I realized the problem was due to the switch not supporting IGMP Snooping, which is essential for handling multicast traffic used by IPTV.

I replaced it with a TP-Link TL-SG108 (V3.0), which works flawlessly. Knowing about IGMP Snooping beforehand would have saved me a lot of time and frustration.

Thanks for the input, Sven. It’s hard to address individual features of a switch, though. Also, that issue can be fixed via the router.

Thanks for your reply. I was unable to fix it on my router, but I might lack the skills.

In any case, many other clients of my IPTV provider (Movistar Spain), have had the same issue when buying switches without IGMP Snooping

I love the work you do. its so informative! thank you so much

Quick question, can I install a switch where my ISP cable comes into my house and use it as a “joiner” so that i can actually put my ISP router elsewhere in the house so that i get better wifi coverage?

my plan was to buy a small high powered unmanaged switch just as a flow through for the internet connection to get to the ISP router which i want to put at the other side of the house?

thanks!

No, Conor, your switch must be behind your router. More here. You can run a long cable from the Internet terminal device to the router, though, and need to run another cable back if you want to put the switch where the terminal device is.

Mr. Dong,

You mentioned (below) that bandwidth sharing occurs within switches, does this also apply also to router ports?

“…suppose the uplink is a Gigabit connection and you have five wired devices connected to a Gigabit switch. In that case, these five devices will share this 1000Mbps link when connecting to the Internet or communicating with any local network device that’s not connected to the same switch. Simple math is that each will get 200Mbps at most when all five are active at the same time.

However, within the switch itself, connected devices can talk to each other without engaging the uplink bandwidth. Specifically, those five devices connected to the switch mentioned above can all talk to one another at full 1Gbps each.”

Yes, Valdo, as mentioned above, a router is basically a layer 3 switch. Make sure you actually read a post in its entirety.

Thank you for your reply, Mr. Dong, seems that I overlooked this information somewhere in the text.

I asked for this to avoid potential issues with the nodes’ Ethernet backhauls.

So it is better to connect the backhaul lines directly into the router ports rather than to concentrate them into one switch and then connect this to one port on the router.

That correct, Valdo, unless you have a switch with a faster uplink connection than the rest of its ports, again, as mentioned.

Sorry, I don’t know what is a 3 layer switch.

I’m just trying to avoid “cascading” switches to maintain the full available bandwidth.

That’s explained in this post, Valdo. Seriously, give it a complete read from top to bottom. It’s not that long.

Layer3 explained yes, for laymen to understand hard.

So, maybe I can get a direct answer. It is better to connect the ethernet backhauls into the router ports 1,2 and 3 or into a switch and then the switch to one of the router ports?

The router ports are 1Gb and the unmanaged switch could be 1Gb or 2.5 Gb.

It generally makes no difference in real-world usage, but you can think of the shared bandwidth as a water delivery system using same/different-size pipes and tanks. The ultimate result depends on how the system is used by how many clients at the same time.

Your consistent answering of questions is appreciated.

I am interested in the difference between the cable types in the 3rd image (POE etc). The one on the right is a RJ45 cable, what is the white, thinner one on the left?

That one is a Ubiquiti Etherlighting cable, Leon. It has transparent connectors and works with the vendor’s Etherlighting ports for easy identification and segmentation.

Thanks Dong!