This post will give you an overview of the Orbi mesh family, Netgear’s popular canned Wi-Fi system.

While a specific Orbi mesh set or router’s performance depends on the particular hardware, it generally shares common attributes in all of the lineup’s variants. So, this post is about the core experience you’ll get from using any Orbi, along with its pros and cons.

By the end of this post, you’ll be able to determine whether the Orbi is a good fit for you among all the different mesh brands.

Netgear Orbi: Dedicated wireless backhaul for the win (until it’s not)

In October 2016, Netgear debuted its Orbi home mesh lineup with the launch of the RBK50. It was a clear winning alternative to the early rise of the eero.

The new mesh system consists of two types of hardware, the primary router (RBR50) and the satellite unit (RBS50), each working only as their specific role. In particular, the router unit can never work as a satellite of another Orbi router and vice versa.

This two-hardware-types-of-specific-roles design has remained since. It’s distinctive from other flexible mesh approaches where users can use multiple (identical) routers—each hardware unit can work as the primary router or a satellite unit.

The use of multiple types of hardware units leads to a naming convention that can be confusing. Let’s dive into that.

Thanks to the initial success of the Orbi line, in September 2020, Netgear introduced the Orbi Pro lineup with the introduction of the SXK80 and the SXK30. This product line shares a similar hardware approach but with a different naming convention not included here.

Netgear Orbi: The evolving naming convention

The naming of Netgear’s Orbi mesh family has evolved over the years. Initially, with Wi-Fi 5 and 6 hardware, a set’s model number starts with RBK—RBK50, RBK13, RBK752, RBK852, and so on. Then, with Wi-Fi 6E, an additional E is added, like in the case of the RBKE960.

In late 2023, starting with Wi-Fi 7, that general convention was changed once more in a major way. Here is the breakdown of how to dissect the name of an Orbi:

Netgear Orbi’s model name (Wi-Fi 7 hardware)

With Wi-Fi 7, Netgear Netgear decided to streamline the hardware naming. Specifically, the company:

- does away with the “K” designation—once used for “kit” as in a system of a router and one or more satellites.

- uses only the number for the series name.

- and differentiates the hardware type (router vs. satellite vs. mesh system) by a role-defining digit.

Take the case of the Orbi 970 Series, for example:

- Orbi 970 Series is the overall name of the new product.

- Orbi RBE97x is the name of particular hardware variant, specfically:

- R = Regular. This is standard hardware without a built-in cable or cellular modem.

- BE = The 802.11be Wi-Fi standard. This is Wi-Fi 7 hardware.

- 97 = The performance grade. This is an internal number decided by Netgear. 97 is currently the highest.

- x= The role-defining digit, specifically:

- x = 0: The RBE970 is the satellite unit—it can’t work by itself and only links to a primary unit to form a mesh system.

- x = 1: The RBE971 is the router unit—it’ll work as a standalone router, the primary unit of a mesh system, but it can’t work as a satellite.

- x = 2 or a higher number: This indicates a mesh system with a router and an x-minus-one number of satellites. So:

- RBE972 indicates a 2-pack mesh: a router + one satellite.

- RBE973 indicates a 3-pack mesh: a router + two satellites.

After that, mesh sets have two suffixes: “B” for the black color and “S” for security, hinting that the hardware includes a one-year trial of Netgear Armor. So the RBE97SB is a 3-pack mesh in black color with built-in one-year security protection.

Netgear Orbi’s model name (Wi-Fi 6E and older)

With Wi-Fi 6E and older hardware, there are three telling things in an Orbi model name: The first letter, the third (and 4th) letter, and the last digit. The 2nd letter is always the same—B is for Orbi.

- The first letter (often R, C, or N, but there might be more) means the hardware’s character.

- R: It’s a regular (standard) setup, be it a single router or a mesh system. So, for example, RBK852 means this one is a standard mesh system.

- C: There’s a cable modem involved. For example, CBK752 is a mesh system in which the router unit has a built-in cable modem.

- N: This is when the router unit is cellular-capable. N here is short for NR, or “new radio,” a fancy name for cellular Internet.

- The 3rd letter (often K, R, or S) means the hardware unit’s exclusive role.

- K = Kit. This means you’re looking at a multi-unit package that includes one router and at least one satellite. So RBK752 refers to a kit of more than one hardware unit. How many? See the last digit below.

- R = Router unit. For example, RBR750 is the router unit of the RBK750 series.

- S = Satellite unit. For example, RBS750 is the satellite unit of the RBK752.

- The 4th letter (if any): That’d be the letter E which stands for Wi-Fi 6E, like the case of the recently announced RBKE960 series.

- The last digit (often 0, 2, 3, etc.) shows the package’s total hardware units.

- 0 = Single hardware unit (either a router or a satellite.) Generally, it signifies a series of hardware releases.

- 2 = A 2-pack (router + one satellite). For example, RBK752 is a 2-pack cable-ready mesh with a CBR750 gateway and an RBS750 satellite.

- 3 = A 3-pack (router + two satellites). The RBK853 is a 3-pack mesh system with one RBR850 router and two RBS850 satellite units.

- The last letter or letters (if any): Most Orbi hardware doesn’t have this last letter. For those that do, it’s intended to add some extra, such as:

- B: This letter means the hardware is black, like the case of the RBKE960B.

- S: It’s for “security,” like the case of the RBR860S, where the unit includes a one-year subscription to Netgear Armor (instead of a 30-day trial.)

- The middle digits (often 5, 75, 85, 96, etc.) are Netgear’s in-house designations to show the hardware’s Wi-Fi specs. They are a bit arbitrary. Specifically:

- 5: This is for Wi-Fi 5. For example, the original RBK50 is a Wi-Fi 5 Orbi.

- 75: This is for a tri-band Wi-Fi 6 with two 2×2 bands and one 4×4 band. Example: the RBK752.

- 85: tri-band Wi-Fi 6 hardware with all 4×4 bands. Example: the RBK850 series.

- 86: The same as the RBK850 series with the router unit having a 10GbE Mult-Gig port (instead of 2.5GbE)—the case of the RBK860 series.

- 96: quad-band Wi-Fi 6E with all 4×4 bands. Example: the RBKE960 series.

For example, the RBRE960 is the standard high-end Wi-Fi 6E router unit of the Orbi RBKE960 series. If you’re still confused, you’re not alone, but you get the general idea.

The pros and cons of the dedicated backhaul band

At its time, the RBK50 was quite revolutionary. It was the first hardware to turn the Tri-band concept (2.4GHz + 5GHz + 5GHz) into practical, effective use. Specifically, the hardware dedicated the 5GHz-2 band—the upper channels—to the job of linking the mesh units. It’s the dedicated backhaul. The system can use the other two bands, the lower-channel 5GHz-1 and the 2.4GHz, to serve clients.

Since no band has to do the backhauling and front-hauling simultaneously, there’s no 50% inherent efficiency loss, which is inevitable in a mesh system without a dedicated backhaul.

In the case of the Orbi, by dedicating the 5GHz-2 band solely for linking the mesh units, which Netgear calls “patented dedicated backhaul”, the company can potentially free it from third-party compatibility and other requirements—the band doesn’t need to work with any application except the link between an Orbi router and its satellite. Consequently, it can be engineered proprietarily for the best possible range and performance.

To maintain the dedicated backhaul approach, the Orbi family generally uses tri-band or quad-band hardware. The RBK13, released in late 2019, is one of a few rare dual-band variants.

A quick refresher: If you’re not familiar with backhauling, the cabinet below includes some highlights.

Mesh in brief: Backhaul vs. fronthaul

When you use multiple Wi-Fi broadcasters—in a mesh Wi-Fi system or a combo of a router and an extender—there are two types of connections: fronthaul and backhaul.

Fronthaul is the Wi-Fi signals broadcast outward for clients or the local area network (LAN) ports for wired devices. It’s what we generally expect from a Wi-Fi broadcaster.

Backhaul (a.k.a backbone), on the other hand, is the link between one satellite Wi-Fi broadcaster and another, which can be the network’s primary router, a switch, or another satellite unit.

This link works behind the scenes to keep the hardware units together as a system. It also determines the ceiling bandwidth (and speed) of all devices connected to the particular satellite Wi-Fi broadcaster.

At the satellite/extender unit, the connection used for the backhaul—a Wi-Fi link or a network port—is often called the uplink. Generally, a Wi-Fi broadcaster might use one of its bands (2.4GHz, 5GHz, or 6GHz) or a network port for the uplink.

When a Wi-Fi band handles backhaul and fronthaul simultaneously, only half its bandwidth is available to either end. When a Wi-Fi band functions solely for backhauling, often available traditional Tri-band hardware, it’s called the dedicated backhaul.

Generally, for the best performance and reliability, network cables are recommended for backhauling—wired backhauling, which is an advantage of mesh Wi-Fi hardware with network ports. In this case, a satellite broadcaster can use its entire Wi-Fi bandwidth for front-hauling.

That said, Orbi has been the performance alternative to wired backhauling and was once considered an ideal choice where you can’t use network cables to link the mesh hardware units. And that has been its strong point. But as time goes by, that’s also slowly become a weakness.

To better understand the Orbi’s permanent backhaul concept’s drawback, you can liken the mesh system’s router unit to a special 4WD pickup truck with a separate engine for the rear wheels dedicated solely to the job of pulling a trailer.

This extra engine makes sense and is great when the truck has a trailer attached (a mesh system) but becomes dead weight when the truck works just by itself (standalone router)—it’s now a full-time front-wheel-drive vehicle. It’s probably not a good idea to consider such a truck unless you intend to use it to pull a trailer at all times.

The point is Netgear’s Orbi only makes sense if you must use a fully wireless mesh Wi-Fi system. When you only need a standalone router or can use a mesh with wired backhauling, any Orbi would be wasteful in terms of hardware cost and energy consumption.

Tri-band mesh systems from other networking vendors might or might not dedicate one of the two 5GHz bands as backhaul, but they generally allow (users to program) all Wi-Fi bands to work for front-hauling. They are 4WD vehicles, whether or not there’s a trailer attached.

Netgear’s latest Orbi set, the 970 Series, a quad-band (2.4GHz + 5GHz + 5GHz + 6Ghz) solution, continues this dedicated backhaul approach. However, considering the vastly superior bandwidth of the new Wi-Fi 7 standard and its new Multi-Link Operation feature, this type of wireless backhauling has proven unnecessary and complicated. Early buyers have reported connection issues, and by the publication of this post, I haven’t yet been able to test it meaningfully for an in-depth review.

Since late 2018, all Orbi hardware has supported wired backhauling—at launch or added retrospectively via firmware updates. In this case, its dedicated 5GHz-2 band is still unavailable for clients. Users waste the upper part of the 5GHz spectrum unless they have a mixed-wired-and-wireless-backaul setup.

It’s worth noting that the exclusion of one of the two 5GHz bands from clients in the Orbi is an issue on top of the common fact in all hardware where the 5Ghz frequency is split into two bands: Each of these bands becomes too narrow to form a wide channel required for high bandwidth.

The Orbi’s hardware (Wi-Fi 6E and older) generally doesn’t support DFS channels. Consequently, its 5GHz bands each have only one 80MHz channel at best, further lowering the bandwidth. The 5GHz is the most important band since it has a longer range than the 6GHz, and most existing clients use it.

A quick refresher: If you’re not familiar with band splitting and DFS, the cabinet below will give you a crash course.

Splitting the 5GHz: The pros and cons

Channels allocation, the 5GHz’s DFS, and band-splitting

A dual-band Wi-Fi 6 (or Wi-Fi 5) broadcaster (2.4GHz + 5GHz) has two distinctive sets of channels. One belongs to the 2.4GHz band, and the other to the 5GHz band.

By default, each channel is set at the lowest width, which is 20MHz. When applicable, the hardware can combine adjacent channels into larger ones that are 40MHz, 80MHz, or even wider.

Again, depending on your locale and hardware, the number of available channels on each band will vary, depending on how wide the band is and the width of the entire band.

In the US, the 2.4 GHz band includes 11 usable 20MHz channels (from 1 to 11) and has been that way since the birth of Wi-Fi. Things are simple in this band. The 2.4GHz band uses channels of 20MHz or 40MHz width. The wider the width, the fewer channels you can get out of the frequency—the entire band is only so wide.

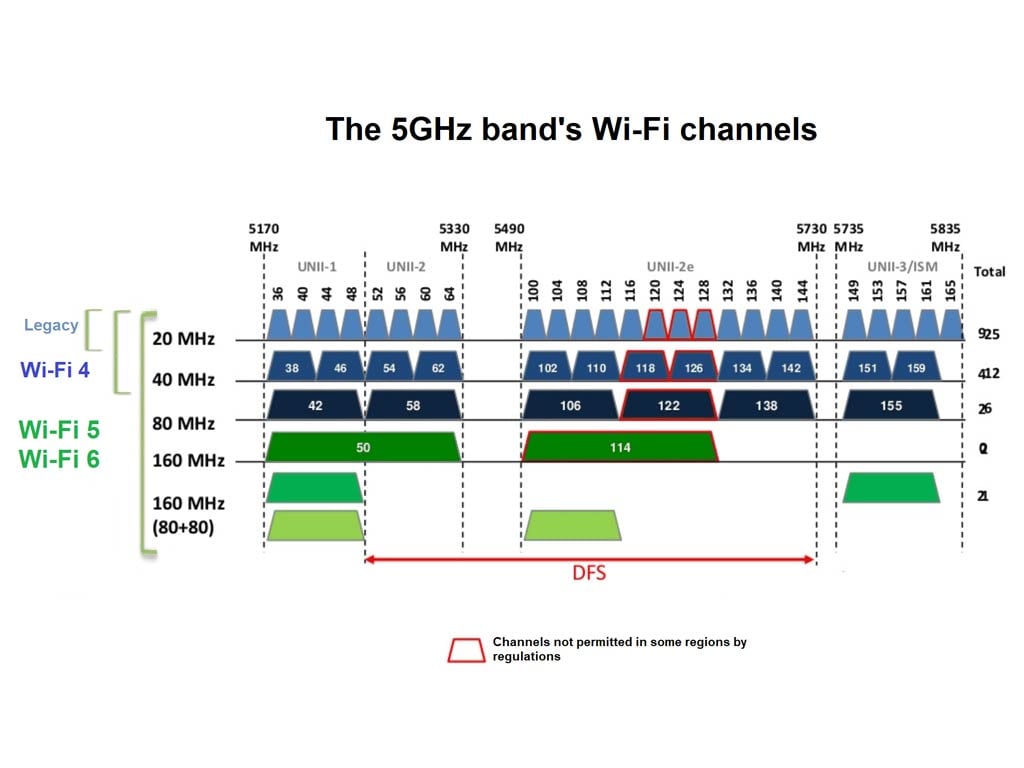

On the 5GHz frequency, regardless of Wi-Fi standards, things are complex. We have DFS (restricted) and regular (non-DFS) channels and the UNII-4 portion. The 5GHz band uses 4 channel widths, including 20MHz, 40MHz, 80MHz, or 160MHz. Wider channels are desirable since they deliver more bandwidth or faster speeds.

Below is the breakdown of the channels on the 5GHz frequency band at their narrowest form (20MHz):

- The lower part of the spectrum includes channels: 36, 40, 44, and 48.

- The upper portion contains channels: 149, 153, 161, and 165.

- In between the two, we have the following DFS channels: 52, 56, 60, 64, 100, 104, 108, 112, 116, 120, 124, 128, 132, 136, 140, and 144. (Channels from 68 to 96 are generally reserved exclusively for Doppler RADAR.)

In a dual-band (2.4GHz + 5GHz) broadcaster, the 5GHz band gets all the channels above (#1, #2). It’ll also get #3 if the broadcaster supports DFS.

In a traditional tri-band broadcaster (2.4GHz + 5GHz + 5GHz), the first 5GHz band (5GHz-1) will get the lower channels (#1), and the 2nd 5GHz band (5GHz-2) gets the upper channels (#2).

If the broadcaster supports DFS, the 5GHz-1 gets up to channel 64, and the rest (100 and up) goes to 5GHz-2. If the hardware also supports the new 5.9GHz portion of the 5GHz spectrum, it generally has three additional channels to its upper part, including 169, 173, and 177.

The splitting of the 5GHz spectrum ensures that the two narrower bands (5GHz-1 and 5GHz-2) do not overlap. So, here’s the deal with traditional tri-band (2.4GHz+ 5GHz+ 5GHz):

- The good: While the total width of the 5GHz spectrum remains the same, we can use two portions of this band simultaneously, theoretically doubling its real-world bandwidth.

- The bad: Each portion (5GHz-1 or 5GHz-2) has fewer channel-forming options, making it harder for them to use the 80MHz or 160MHz channel widths required for high bandwidth. Physically, the channel-width options are now more limited than when the entire 5GHz spectrum is utilized as a single band.

- The bottom line: Limited bandwidth for each sub-5GHz band. In an area crowded with 5GHz Wi-Fi broadcasters, practically everywhere these days, this band-splitting practice likely adds little in terms of extra real-world total bandwidth.

Netgear Orbi: Full web interface, optional mobile app, or vice versa?

Like the case of the Linksys Velop, the Orbi has a full local web user interface and the Orbi mobile app, originally available as an option.

In mid-2019, Netgear introduced Netgear Armor online protection as an add-on subscription for its Orbi mobile app. Depending on the model, this is often included as a month-long or year-long trial period. Additionally, there’s a separate subscription for the Parental Control feature.

Unfortunately, since then, Netgear has slowly removed useful features and settings from the web user interface, and these once-free elements are part of the subscription. The moment you set up a new Orbi, you’ll be coerced into signing up for a login account and using the mobile app.

A barebone set of Wi-Fi and network settings

Without an Armor subscription and the use of a mobile app with a login account, Orbi hardware is rather modest in terms of features and settings.

Generally, the hardware provides a limited set of network settings. Specifically, there are DHCP settings, Dynamic DNS, port forwarding, OpenVPN (in select models), etc., and that’s about it.

There’s no common stuff, part of which was once available for free, such as QoS, parental control, online protection, and remote web-based management. Additionally, you generally need to use both the local web interface and the mobile app to get things done—neither can be the complete management solution that gives you everything.

For example, the Orbi mobile app doesn’t have access to port-forwarding or dynamic DNS settings, and the web interface has no remote access, Parental Control, or online protection. In short, the tendency to turn the hardware app-operated has slowly made the Orbi and other Netgear routers less useful than they once were.

In terms of Wi-Fi settings, the Orbi hardware is also limited. Specifically for the main Wi-Fi network:

- Wi-Fi 6 and older: You can’t use separate SSIDs for the 5GHz and 2.4GHz bands. Smart Connect is the only option. No DFS support.

- Wi-Fi 6E: The 6GHz band can have an SSID of its own. No DFS support.

- Wi-Fi 7: Smart Connect is the only option for all bands, and the 5GHz band has DFS support.

Other than the main SSID, all Orbi hardware comes with a single Guest SSID for the 2.4GHz and 5GHz bands. Wi-Fi 6E and newer hardware also include an IoT SSID (2.4GHz and 5GHz), which is a virtual network designed for segmenting low-bandwidth smart devices.

Netgear Orbi Mesh System's Overall Rating

Pros

Overall reliable Wi-Fi with extensive coverage for a fully wireless setup; wired backhauling support

Full web interface with standard settings and features

Useful, well-designed mobile app

Wi-Fi 6 and newer hardware comes with Multi-Gig support

Cons

High cost; high lag tendency; the dedicated backhaul band can't host clients even in a wired backhaul configuration

Limited Wi-Fi customization; Wi-Fi 6E and older hardware has no 160MHz channel width on the 5GHz band

No cross-Wi-Fi standard hardware compatibility; the router unit can't work as a satellite

Subscriptions, mobile app, and login account are required for helpful features, such as security, parental control, or VPN; lots of upselling nags

Conclusion

On the one hand, if you have gotten your home wired, Orbi is never a good choice financially—you’ll lose half of the 5GHz bandwidth for nothing. So consider one only if you intend to use it in a wireless configuration.

In this case, note that its performance is generally limited by its wireless backhaul. For Wi-Fi 6E and older hardware, this backhaul occupies only half of the frequency while not supporting DSF. As a result, its highest bandwidth is limited by the 80MHz channel width to cap at 1202Mbps of theoretical speed. Wi-Fi 7 hardware, such as the super-expensive 970 series, has a major improvement on the backhaul band thanks to the MLO feature. Still, over a long distance, this backhaul link still depends on the upper portion of the 5GHz band.

Another thing to note is that Orbi, in a wireless setup, tends to have lag (latency) issues. So, it’s not ideal if you want to play online games or use real-time communications (video conferencing, etc.). The lag issue is especially prevalent if you use three or more hardware units in a daisy-chain topology.

On the other hand, like all mesh systems, wired backhauling is still the only way for the Orbi to deliver the best performance, especially in hardware with a Multi-Gig port. So, in the end, the Orbi family is best applicable to a home where you need to mix wired and wireless setups. It’s the only time the permanent backhaul band is justified in terms of both performance and cost.

Dong: Like you, I live in NorCal and subscribe to Xfinity Extreme Gigabit Internet. I get more than 1,300 Mbps at the cable. But my Netgear Orbi RBR760 mesh system only gives me a maximum of 700 Mbps to my devices.

Short of wiring my house, which isn’t going to happen, is there any way I can get faster speeds on my mesh network? I’m frustrated that the Orbi system is only giving me about half the speed that I’m paying for…

That’s about as fast as you can get via any Orbi, Michael. Maybe try MoCA backhauling.